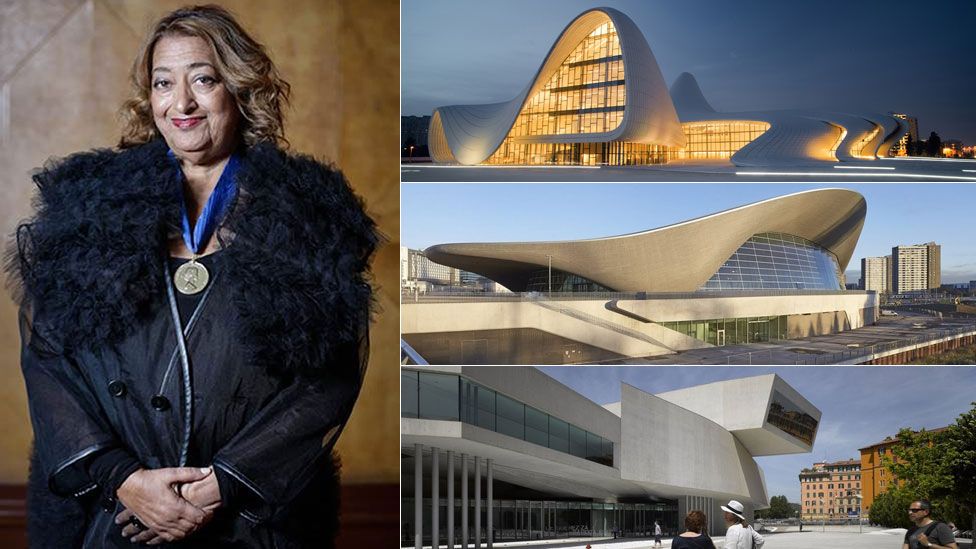

How Zaha Hadid Has Changed The Realm Of Architecture

Zaha Hadid, one of the pioneers of modern architecture has set new limits as to what an architect can create. According to her own mentor, Ram Koolhaas, she “is a planet in its own orbit.” She created the path for future female architects to thrive in this male-dominated industry, becoming the first woman to be awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize, often regarded as the Nobel Prize of architecture. Furthermore, she was described by The Guardians as the “Queen of the curve”, who “liberated architectural geometry, giving it a whole new expressive identity.”

Early life and career

Zaha Hadid – in full, Dame Zaha Hadid – was born on October 31th, 1950 in Baghdad, Iraq. She began her studies at the American University in Beirut, Lebanon receiving a bachelor’s degree in mathematics. Her architecture journey officially began in 1972 at her studies at the Architectural Association, a major centre of progressive architectural thought during the 1970s. There she met the architects Elia Zenghelis and Rem Koolhaas, both inspired by her brilliancy and endless creativity, focusing on the broader picture.

After graduation, Hadid collaborated with her former two professor architects Zenghelis and Koolhaas, as a partner at the Office of Metropolitan Architecture. Later in 1979 Hadid established her own London-based firm, Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA) – marking the beginning to her endless road of fame, success and acknowledgement for her timeless projects.

Gaining international recognition

In 1983 through her competition-winning entry for The Peak – a leisure and recreational centre in Hong Kong, Hadid managed to gain herself international recognition, creating a spark soon to be followed by a burning fire. This design, a “horizontal skyscraper” established her original aesthetic: inspired by Kazimir Malevich and the Suprematists, her aggressive geometric designs are characterised by a sense of fragmentation, instability, and movement. This fragmented style led her to be grouped with architects at the time, known as “deconstructivists.”

This design however, along with most of her other radical designs in the 1980s and early 1990s – the Kurfürstendam (Berlin), the Düsseldorf Art and Media Center, and the Cardiff Bay Opera House (Wales) – were never properly recognised. She started off being known as a “paper architect” – defined as someone whose designs were too avant-garde to move beyond the sketch phase and be built into actual buildings. However, Hadid proved the world wrong with her first built projects that made way for some of the most timeless buildings to be created in the 20th and 21st centuries.

First built projects

Hadid’s first major built project was the Vitra Fire Station, 1993 in Weil am Rhein, Germany. This build was composed of a series of sharply angled planes, resembling a bird in flight and reflecting on her style of “deconstructivism.” Other works from her during this period included a housing project for IBA Housing in 1993, Berlin, the Mind Zone exhibition space (1999) at the Millennium Dome in Greenwich, London, as well as the Land Formation One exhibition space in 1999 again in Weil am Rhein. Through all these major projects, Hadid further explored her interest in creating interconnecting spaces and a dynamic sculptural form of architecture.

Hadid further solidified her reputation as an architect of built works in the 2000’s, during work on her design for a new Lois & Richard Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati, Ohio. Later on, this museum opened in 2003 became the first American museum designed by a woman – and as ironic as it was, an Iraq-British woman. Essentially a vertical series of cubes and voids, the museum is located in the heart of Cincinnati’s downtown area, inviting passersby in with a translucent glass facade on the side of the building that faces the streets. This helped to contradict the previous notion of the museum as an uninviting or remote space. Additionally, the building’s plan gently curves upward after the visitor enters – Hadid said she hoped this would create an “urban carpet” that welcomes people into the museum.

Breakthroughs in the industry

In 2010 with the breakthrough of a boldly imaginative design for the MAXXI museum of contemporary art and architecture in Rome, Hadid was able to earn the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) Stirling Prize for the best building by a British architect completed in the past year. This was followed by a second Stirling Prize in the following year for a sleek structure she conceived for Evelyn Grace Academy – a secondary school in London.

Her remarkable awards and acknowledgements didn’t stop there, as the world finally fully realised what she was able to offer them. Hadid soon became the first woman to earn the London Design Museum’s Design of the Year award in 2014, for her fluid undulating design for the Heydar Aliyev Center – a cultural centre that opened in 2012 in Baku, Azerbaijan.

Controversies

All of her extraordinary accomplishments were all the more remarkable considering she was working in an industry highly dominated by men. This left her vulnerable to many more controversies that her male counterparts were subjected to, yet it only further paved the path for future aspiring woman architects to take on their passions for the field and fight their way for equal virtue.

Examples of persecution she faced include the ridicule of the expense and scale of many of her commissions, as well as the derision of her fantastic forms. Mounting protests, notably from preeminent Japanese architects led her to scrap her plan altogether for the New National Stadium for the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo, that was postponed to 2021 due to the covid-19 pandemic.

Further controversy followed after a 2014 report disclosed that some 1,000 foreign workers had dieddue to poor working conditions across construction sites in Qatar, where her Al Wakrah Stadium (later the Al Janoub Stadium) for the 2022 World Cup was set to break ground – as stated by Britannica. When asked about the deaths, Hadid objected to her responsibility as an architect to ensure safe working conditions, and her remarks were widely regarded as insensitive. An architecture critic of The New York Review of Books exacerbated the situation when he falsely claimed that 1,000 had died building her stadium, which had yet to break ground. Hadid filed a defamation lawsuit against the critic and publication. She later settled, accepting an apology and donating the undisclosed sum to a charity protecting labour rights.

Impacts made…

At her sudden death in 2016 from a heart attack while being treated for bronchitis, Hadid left a number of unfinished projects. Her business partner, Patrik Schumacher, who assumed leadership of her firm, assured the completion of these existing commissions and the procurement of new ones. Her trustworthy firm, ZHA managed to do what Shumacher promised, and stamped out such unfinished projects as the Antwerp Port House (2016), the King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center (2017; KAPSARC), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and the Al Janoub Stadium (2019), before the end of the decade.

Today, her legacy made as a world renowned architect don not just live through her established firm or breathtaking architecture, but also through her modern, cutting edged philosophies that have helped her push through the boundaries of architecture and design, proving to us that nothing is impossible.

Bibliography

- Zukowsky, John. “The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire | British Order of Knighthood.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 16 Nov. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/topic/The-Most-Excellent-Order-of-the-British-Empire.

- Jessica. “10 Inspirational and Architectural Lessons from Zaha Hadid.” MYMOVE, 21 Sept. 2012, https://www.mymove.com/home-inspiration/architectural/inspirational-and-architectural-lessons-from-zaha-hadid/.

- Muse, Curious. “Top 5 Modern Architects Explained: Who Is Shaping Today’s Cities?” Www.youtube.com, 27 Nov. 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s3qB8LyWeEg.

- Li, ZiQing. “MyBib – a New FREE APA, Harvard, & MLA Citation Generator.” MyBib, 19 Dec. 2022, https://www.mybib.com/#/projects/Wr3r7e/citations.

One Comment

zoritoler imol

Thank you for the good writeup. It in fact was a amusement account it. Look advanced to far added agreeable from you! However, how can we communicate?